Coasting Towards Catastrophe

Shannon Cochrane, Photo: Antti Ahonen

Shannon Cochrane, Photo: Antti Ahonen

PAO Festival 2017

By Vilde M. Horvei

«This is a boat, and we’re all in it together» Shannon Cochrane announced, while moving a small paper boat glued to the inside of a passport over a table covered by a blue sheet. Cochrane’s work, which was the first performance on the third day of the Performance Art Oslo Festival 2017, was a timely reference to the constant movement of people under contemporary capitalism and the toll it is taking on the environment. Cochrane’s remark was an apt reminder that we are all part of this not-so-fruitful development. Reflecting on the festival some days later, it struck me that her remark was equally relevant as a metaphor for the festival itself.

For three intense days, the audience of Performance Art Oslo (PAO) witnessed twelve performances, six artist presentations and a number of student performances from Performance Art Studies (PAS). For those of us that experienced the entire festival, it undoubtedly felt like being together in a boat. This journey, though demanding in terms of duration, gathered people from various countries with different interests. Inside the walls of ROM – the Oslo art space where the festival was taking place – The feeling of a community growing was very much apparent.

By Vilde M. Horvei

«This is a boat, and we’re all in it together» Shannon Cochrane announced, while moving a small paper boat glued to the inside of a passport over a table covered by a blue sheet. Cochrane’s work, which was the first performance on the third day of the Performance Art Oslo Festival 2017, was a timely reference to the constant movement of people under contemporary capitalism and the toll it is taking on the environment. Cochrane’s remark was an apt reminder that we are all part of this not-so-fruitful development. Reflecting on the festival some days later, it struck me that her remark was equally relevant as a metaphor for the festival itself.

For three intense days, the audience of Performance Art Oslo (PAO) witnessed twelve performances, six artist presentations and a number of student performances from Performance Art Studies (PAS). For those of us that experienced the entire festival, it undoubtedly felt like being together in a boat. This journey, though demanding in terms of duration, gathered people from various countries with different interests. Inside the walls of ROM – the Oslo art space where the festival was taking place – The feeling of a community growing was very much apparent.

Henrik Koppen, Photo: Antti Ahonen

Henrik Koppen, Photo: Antti Ahonen

The boat metaphor also holds true of what PAO has become during their five years of existence, a closely-knit community based on collective experimentation, dialogue and exchange of ideas. By establishing the festival as a yearly event, the organisation has found its distinct path within the vast spectrum of performative tendencies. The fifth edition displayed performances which utilised a visually poetic language, in which abstract symbolic elements are composed in a durational and repetitive manner. Visual poetics have been a recurring element in several of PAO’s earlier editions. Other recurring themes amongst this year’s performances was their shared connection to our contemporary social-, ecological and political situation.

Taking the connection with nature literally, Henrik Koppen unsuccessfully attempted to merge himself with nature through actions such as using tar as perfume. As the room began to smell a lot like bleeding trees, a large fire was projected on the wall. The atmosphere created by this scenery was relaxing, but it also had a vague sense of fakeness to it. In fact, the projection, coupled with the smell of tar, resembled the forced ‘cosiness’ of a fire-place substitute video for TV. The performance contained several tropes typical of Norwegian history and culture, which only reinforced the futility of Koppen’s struggle to get closer to a non-existent stereotypical and idealised version of nature and Norwegian folklore.

While Cochrane and Koppen’s works dealt with our contemporary connection to nature and natural resources, other works were aiming their frustration towards specific political issues. In Kevin Meehan’s Rain Delay the target was the political situation in the United States. With a straight back attitude, dressed in a red plaid shirt, white t-shirt and blue Levis jeans, Meehan took on the role of a stereotypical white working-class male. With a bucket full of fresh meat, he positioned himself in the stance of a baseball pitcher and repeatedly threw meat at a white wall. Meehan’s performance included a six-pack of the beer Budweiser - a brand criticised by Trump-supporters for their 2017 Super Bowl commercial portraying the immigrant founder of the popular brand. An interesting aspect is how something as embedded in the American culture as baseball and Budweiser is being strategically used for – and against – political positions. The baseball pitcher becomes powerless, a puppet in a political game where not even a beer brand can stay neutral.

Taking the connection with nature literally, Henrik Koppen unsuccessfully attempted to merge himself with nature through actions such as using tar as perfume. As the room began to smell a lot like bleeding trees, a large fire was projected on the wall. The atmosphere created by this scenery was relaxing, but it also had a vague sense of fakeness to it. In fact, the projection, coupled with the smell of tar, resembled the forced ‘cosiness’ of a fire-place substitute video for TV. The performance contained several tropes typical of Norwegian history and culture, which only reinforced the futility of Koppen’s struggle to get closer to a non-existent stereotypical and idealised version of nature and Norwegian folklore.

While Cochrane and Koppen’s works dealt with our contemporary connection to nature and natural resources, other works were aiming their frustration towards specific political issues. In Kevin Meehan’s Rain Delay the target was the political situation in the United States. With a straight back attitude, dressed in a red plaid shirt, white t-shirt and blue Levis jeans, Meehan took on the role of a stereotypical white working-class male. With a bucket full of fresh meat, he positioned himself in the stance of a baseball pitcher and repeatedly threw meat at a white wall. Meehan’s performance included a six-pack of the beer Budweiser - a brand criticised by Trump-supporters for their 2017 Super Bowl commercial portraying the immigrant founder of the popular brand. An interesting aspect is how something as embedded in the American culture as baseball and Budweiser is being strategically used for – and against – political positions. The baseball pitcher becomes powerless, a puppet in a political game where not even a beer brand can stay neutral.

Although several works presented during the festival referenced contemporary societal issues, none of them argued for a way out of this disarray. Thankfully, while we might have reached the point of no return regarding our prospects, Ida Grimsgaard’s humoristic parody of societal issues represented a welcome moment of relief. Entering the room to cheerful music, dressed in a blond wig and a white nightgown while carrying seven shopping bags, she looked like she’d taken conspicuous consumption to a whole new level. But rather than her latest bargain, she pulled out seven identical fabric dolls, one from each of the bags. The dolls, which were close to identical replicas of her appearance – both wig and nightgown – were then tucked around her body. Despite her comical appearance, the multiplication of herself indicated a scepticism towards consumer culture and the effect it has on our sense of identity. With the bundle of bodies folded around her own body, the original could no longer be separated from her copies, thereby erasing any sign of a personal identity. Using the age of social media as a backdrop – without anywhere to hide from someone telling you how to look, what to do and how to behave – it might not come as a surprise that conformity is more sought after than uniqueness.

Ellakajsa Nordström & Ylva Trapp, Photo: Antti Ahonen

Ellakajsa Nordström & Ylva Trapp, Photo: Antti Ahonen

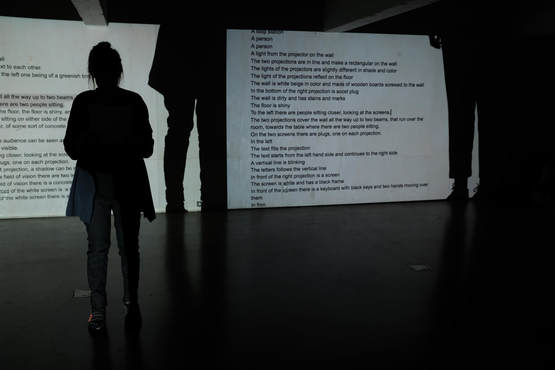

A society where both social relations and consumerism are shaped by the constant flow of information, testifies to how dependent on communicative tools we’ve become. Speed, omnipresence and constant feedback from friends and acquaintances are essential to how we communicate and experience the world. Presenting a somewhat cerebral performance, the duo Ellakajsa Nordström & Ylva Trapp addressed the relationship between sensory perception, language and meaning as communication. The work, The path taken between two points by a ray of light is the path that can be traversed in the least time, borrows its title from a mathematical principle used to describe the properties of light rays, discovered by French mathematician Pierre de Fermat (1607 – 1655). Light rays came to life through two different coloured projections on the wall, displaying texts being written and reformulated in real-time. Each text gave a similar, but not identical, description of the room’s interior (people, colours, shapes etc.), before they were orally fragmented, abstracted through visual modification and finally deleted. It was as if language, our main communicative tool, was erased altogether.

Mia Øquist, Photo: Antti Ahonen

Mia Øquist, Photo: Antti Ahonen

Taken together, the performances of PAO 2017 were pessimistic about the future. This bleak outlook was most notably present in Mia Øquist’s performance. In Soft Claustrophobia she showed the audience visual maps coinciding with the structure of a black fabric tunnel that circled the room and audience. The tunnel resembled a mole’s windy pathway, which Øquist then started crawling through. As she struggled with navigating the dark and claustrophobic confines of the fabric she had to untwine it from the audience, benches and pillars in the room. When she finally reached the end of the path, the exit turned out to be sewn shut. Øquist was forced to repeat the entire process, struggling back to her point of entry.

And maybe this is it. We might be stuck on an unavoidably dead-end path, using up all our natural resources, erasing both language and ourselves. The claustrophobic distress in Øquist’s performance, coupled with Koppen’s desperate need to get closer to nature is warning us that the boat Cochrane eloquently placed us in is sinking. The urgency in the issues the artists of the PAO festival 2017 touched upon, very much felt like a distress signal – either we face global political-, ecological- and social crises now or it will quite possibly be the end of human existence.

And maybe this is it. We might be stuck on an unavoidably dead-end path, using up all our natural resources, erasing both language and ourselves. The claustrophobic distress in Øquist’s performance, coupled with Koppen’s desperate need to get closer to nature is warning us that the boat Cochrane eloquently placed us in is sinking. The urgency in the issues the artists of the PAO festival 2017 touched upon, very much felt like a distress signal – either we face global political-, ecological- and social crises now or it will quite possibly be the end of human existence.