PAO@Steilene

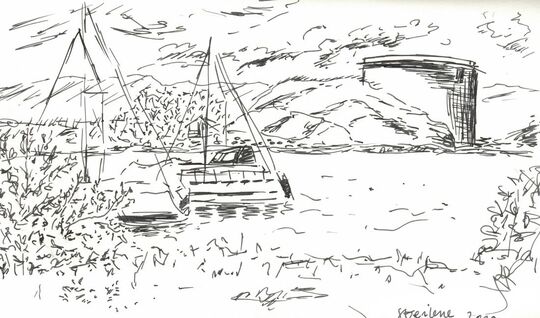

Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

Text about PAO@Steilene 2019 by Alicja Rosé

Each time i leave the steep slope of Nesodden behind me, the west side of the peninsula which enters the Oslofjord like, nomen omen, a long nose, or the long snout of an alligator half immersed in sea water, its russet, brown rocks unshaved, shaggy with pines, rocks coming from Precambrian times, 250 million years ago, sedimentary rocks, and i head over to the five islands of Steilene, i have the feeling i am abandoning earth to reach a planet that is holding a secret.

At first sight it feels that it will be easily revealed to you. The islands are thin and long like five dolphins´ backs sticking out of water. Easy to catch in the glimpse of an eye. Somewhat tangible when Tom Sammerud, who works on Steilene on behalf of the Nesodden kommune, transfers me in his boat as if it was the ferry from the Chekhov story “Easter Eve.” I just await Tom turning out to be that same Ieronym who, on this holy night, shall transfer men, women and children between two shores of the river, to and from the congregation in a monastery there, and who shall tell me of the death of an old monk from the monastery, gifted with writing exceptional Akathist hymns that only Ieronym could appreciate. Yes, we are about to embark on an observance.

Performance by Franzisca Siegrist - PAO@Steilene 2017. Photo: Jon Marius Nilsson

Performance by Franzisca Siegrist - PAO@Steilene 2017. Photo: Jon Marius Nilsson

The islands on either side of Nesodden, when looked upon from the sky or simply seen on a map, seem like its fens, additional punctuation signs. They seem easy to understand, almost barren, walkable. It is Franzisca Siegrist who welcomes me warmly on the shore, an artist of Swiss and Canary Island background, who is one of the founders of Performance Art Oslo (PAO). She reaches out with her arm to me to help me step out of the boat as if she was giving me a thread, like Ariadne, to help me go through the labyrinth of Steilene island – as in fact she once did, two years ago, in her own performance, walking thin paths here with a string attached to her body and unraveling a big bundle left behind her, like a tail. This is the fifth time PAO invites us to the islands.

I recognize dark rocks interwoven with light ones, feathers arranged diagonally and mounting up like steps. Stones are said to be indifferent. Stones, said Bartholomeus Anglicus, the early 13th-century scholastic in Paris who wrote a huge compendium on almost everything, including stones (De proprietatibus rerum, or On the Properties of Things), are “bones of the earth.” They are said to be silent, deaf, tough, steady. They are said to be obstacles. Yet, we are connected. Milestones are the core of our history, or we are just a tiny part of theirs. When looked upon more closely, they speak. They tell us stories of troubled times of the Permian, when Oslofjord sank like the Titanic, when the bedrock of the peninsula had cracked. The molten volcanic mass had seized that moment and filled in the gaps then solidified over time. Down at the bottom, the pressure and temperatures transformed the rocks. Clay slate turned into gneiss and mica, the granite crystallized. We now see veins of quartz running through dark rocks.

But Steilene reappeared after tectonic movements, their clay and limestone rock folded like a fabric. They are pure, untransformed, archetypical. They come from the Ordovician Period, a term coined by English geologist Charles Lapworth (1842–1920) from the Latin Ordovices, an ancient British tribe in North Wales. Its rocks were first studied extensively in the region around Bala in North Wales. The Celtic name of the tribe tells us about "those who fight with hammers," from Celtic base ordo, or "hammer," and the Proto-Indo-European root weik, "to fight, conquer." As we have always assumed we have conquered lands we inhabit.

It is a hot day, and through the translucent water i can see algae swinging softly like Jewish men at prayer time. I immerse myself and swim around the very tip of the island, where Jan-Egil Finne, an artist from Bergen, is standing with his feet down in water up to his ankles, trying to hold his balance.

I recognize dark rocks interwoven with light ones, feathers arranged diagonally and mounting up like steps. Stones are said to be indifferent. Stones, said Bartholomeus Anglicus, the early 13th-century scholastic in Paris who wrote a huge compendium on almost everything, including stones (De proprietatibus rerum, or On the Properties of Things), are “bones of the earth.” They are said to be silent, deaf, tough, steady. They are said to be obstacles. Yet, we are connected. Milestones are the core of our history, or we are just a tiny part of theirs. When looked upon more closely, they speak. They tell us stories of troubled times of the Permian, when Oslofjord sank like the Titanic, when the bedrock of the peninsula had cracked. The molten volcanic mass had seized that moment and filled in the gaps then solidified over time. Down at the bottom, the pressure and temperatures transformed the rocks. Clay slate turned into gneiss and mica, the granite crystallized. We now see veins of quartz running through dark rocks.

But Steilene reappeared after tectonic movements, their clay and limestone rock folded like a fabric. They are pure, untransformed, archetypical. They come from the Ordovician Period, a term coined by English geologist Charles Lapworth (1842–1920) from the Latin Ordovices, an ancient British tribe in North Wales. Its rocks were first studied extensively in the region around Bala in North Wales. The Celtic name of the tribe tells us about "those who fight with hammers," from Celtic base ordo, or "hammer," and the Proto-Indo-European root weik, "to fight, conquer." As we have always assumed we have conquered lands we inhabit.

It is a hot day, and through the translucent water i can see algae swinging softly like Jewish men at prayer time. I immerse myself and swim around the very tip of the island, where Jan-Egil Finne, an artist from Bergen, is standing with his feet down in water up to his ankles, trying to hold his balance.

|

How am i to adjust myself to the rock

how am i to take its shape on as if putting on a cloak how am i to feel it how am i to attach myself i am a vertebrate again a small crab a tightrope walker on a firm land hard to grasp hard to find balance hard to fit in hard to snuggle in hard to be cuddled i place my head, a prodigal son from the Rembrandt painting placing his head in his father’s palms i cling with my feet to feel the smell will it receive me i cling with my fingers i wish my feet were gloves i wish my journey was a prayer or an act of penance in face of the island its congealed waves of lava |

Performance by Pavlina Lucas, Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

Performance by Pavlina Lucas, Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

“I have a pebble in my shoe / and I can’t stop dancing” Ella Fitzgerald sings, and Jan-Egil Finne, the crab acrobat, cannot stop balancing on the stones as if he was singing instead “Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you join the dance?” from the "Lobster Quadrille" of Lewis Carroll. But we join Fernanda Branco, an artist from Brazil, who guides us with her arms moving gently. Her stripes of white hair among black correspond with light and dark stripes of lava. Two years ago, she had spread the lightness of salt around the rocks when trying to understand how water becomes salt, how the salt goes back to water. Fernanda later tells me a secret Brazilian recipe against heat stroke: “It is called sur, a glass of water with sugar and salt, dissolved. But i need to check the exact dose and will tell you later.” The measurements and quantities are crucial. The correct quantity of salt in the water.

Steilene from afar look like a snail with a chimney instead of a shell. It used to be an armored ship, a cuirassier, a big warlike vessel, full of concrete oil tanks stacked on its back. Now we step into a remnant, a concrete circle where Pavlina Lucas, an artist and architect from Greece, placed ice cubes in its center then in lines which form a cross, a symbol of farewell, to a melting world. Pavlina, like Sisyphus, replaces ice, which is melting quickly in the sun, with new cubes, as once the writer Witold Gombrowicz, at the ocean shore, turned over beetles lying on their backs and desperately moving their legs in the air, replacing them back in the sand, an endless number of beetles, a mission never accomplished. Pavlina tries to win the race with time, outguessing Zenon and his paradoxes.

Steilene from afar look like a snail with a chimney instead of a shell. It used to be an armored ship, a cuirassier, a big warlike vessel, full of concrete oil tanks stacked on its back. Now we step into a remnant, a concrete circle where Pavlina Lucas, an artist and architect from Greece, placed ice cubes in its center then in lines which form a cross, a symbol of farewell, to a melting world. Pavlina, like Sisyphus, replaces ice, which is melting quickly in the sun, with new cubes, as once the writer Witold Gombrowicz, at the ocean shore, turned over beetles lying on their backs and desperately moving their legs in the air, replacing them back in the sand, an endless number of beetles, a mission never accomplished. Pavlina tries to win the race with time, outguessing Zenon and his paradoxes.

Performance by Frauke Materlik. Photo: Jon Marius Nilsson

Performance by Frauke Materlik. Photo: Jon Marius Nilsson

The only tank that remains, in the very middle of the island, has a hole, tricky to enter. I enjoy watching curious dogs sticking their heads in, with tails wagging happily outside, or their owners, women in fine dresses, sticking their bottoms towards those left outside, and letting the wind, now blowing harder, ask their skirts to dance. The concrete chimney is a relic. The island used to hold tanks that belonged to an oil company established here in the early 20th century. On the neighboring island to the east, a factory was built, along with a house, a school. Families came. Men worked. Women took care of homes. They lived this secluded life. There is a circle of bricks next to the building. “What is it?” i ask Tom. Who knows. We joke that it might be some Stonehenge, which will puzzle visitors in years, many years, to come. On the fifth island, far to the west, a man took care of the lighthouse. He lived there with his family for decades, alone. There is no water there. No water on Steilene either. Unless you like it salty.

The tank is a resonator. It can amplify the voice in a cante jondo song, sung by Johanna Zwaig, and spread it all across the island. But it can also serve as a stage, an intimate theater, with one actor, Frauke Materlik, a German artist living in Norway, in its center, placing stones on a long sheet of paper rolled out then learning to place her feet in between, calligraphing signs with a black paint resembling tar, as if she was finding herself in a new space, as if she was walking blind on a street, a butoh dancer or a child sneaking at night to the kitchen for a treat. The wind outside grows harder. I recall the vocal and instrumental duet of artists Yendini Yoo Cappelen and Marie Kaada Hovden one year ago here, who sat outside the tank on the rocks and accompanied the wind and its blowing sounds so finely, unless it had been accompanying them.

Performance by Susanne Irene Fjørtoft, Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

Performance by Susanne Irene Fjørtoft, Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

When i step forth from the tank, i struggle against the wind as if i was dragging big stones on strings, as Susanne Irene Fjørtoft was doing, an artist originally from Ålesund. I recall the place where smart seagulls hunted for our snacks two years ago, and how i had to push the wind and pull my solo audience members every hour from the east side of the island, where they awaited me in the shade of a dainty tree, then lead them blindfolded to the very tip, at the opposite side. I had been following the script of Liv Kristin Holmberg, a performer and harpsichord player. They had to learn their steps like children and the rough back of the island didn’t make this tricky education simple for them. A paraglider landed on my way, ate his lunch and happily fell asleep. If only he dreamt of the endeavor he had added to my abstract struggle.

Each time i walk this path i cannot grasp the mystery it withholds. The lack of tanks left no trees but one, a small, slender white birch standing there like a ghost or an abandoned bride, among grass and violet flowers of veronica (meaning: a true look) and white mountain-stone parsley, with such a name it could not grow elsewhere. A tall white triangle moving from north to south tells me there is a boat attached to it. Or was it a cloud? When you walk in opposite direction, you reach the very tip. This is where i had placed a chair and my blindfolded audience so that they could receive the cleansing ritual of the Last Oil, as Liv Kristin Holmberg titled it, according to old Orthodox rituals. That oil serves for cleansing. The one that was once stored here served instead in the opposite way, but yes, it also lit our lamps. Don Lawrence, one of my audience then, a performer himself and an architect, had opened his eyes to see the ocean. He would tell me later how it inspired him for a new architecture project. This is the place you really meet the ocean, or yourself.

Each time i walk this path i cannot grasp the mystery it withholds. The lack of tanks left no trees but one, a small, slender white birch standing there like a ghost or an abandoned bride, among grass and violet flowers of veronica (meaning: a true look) and white mountain-stone parsley, with such a name it could not grow elsewhere. A tall white triangle moving from north to south tells me there is a boat attached to it. Or was it a cloud? When you walk in opposite direction, you reach the very tip. This is where i had placed a chair and my blindfolded audience so that they could receive the cleansing ritual of the Last Oil, as Liv Kristin Holmberg titled it, according to old Orthodox rituals. That oil serves for cleansing. The one that was once stored here served instead in the opposite way, but yes, it also lit our lamps. Don Lawrence, one of my audience then, a performer himself and an architect, had opened his eyes to see the ocean. He would tell me later how it inspired him for a new architecture project. This is the place you really meet the ocean, or yourself.

Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

Illustration by Alicja Rosé, Steilene 2019

When a week later i am passing the islands on a ferry along their west side, i try to imagine the construction of torture device, a pole and a wheel or a steile og hjul, as it was called, from which peaceful-looking Steilene took the name. This was a place of execution in the 19th century. It is where Norwegian law was put into practice as a warning to boats and ships and their crews who might be dreaming of bounties as they sail by. They would see from their decks those tall poles with wood wheels on top, and corpses of men on top of them. While deep beneath me, wrecks of ships sleep on the bottom. At the very bottom, foraminifera live, our ancestors, protists, literally “hole bearers” (from Latin), as their shells are elaborately shaped with many chambers. They tell us, as stones do, about the past, but also about the present. The very bottom is polluted and it will take a long time to become clean again.

I remember sitting with Fernanda, after a marvelous and delicious dinner, as always, on the stairs on the west side of the house, where the wind does not have easy access, looking towards the main island of Steilene, with its hunchback, holding stones gathered that day by the Danish artist Rasmus Jensen on the rocky beach, as if holding someone’s hand. We constitute a petric tandem, establishing a lapidary connection, we are entangled and intertwined like the trunks of willows growing next to the house. The root of the word stone is solid, stoi-no-, the suffix form of the root stai- or "stone," also "to thicken, stiffen" (the source also of Sanskrit styayate, "curdles, becomes hard," while the Greeks meant a "fat, tallow,", and behind stia, stion, they meant what we do when we say "pebble." A stone was a measure of weight. A petrified testicle. A source of imagination. The stone i find at the north tip of the island, covered in cotton material by Susanne Irene Fjørtoft, looks like the pillow which served Jacob in his sleep and brought him a vision. Or it is a challenge for struggling, frustrated sculptors.

I remember sitting with Fernanda, after a marvelous and delicious dinner, as always, on the stairs on the west side of the house, where the wind does not have easy access, looking towards the main island of Steilene, with its hunchback, holding stones gathered that day by the Danish artist Rasmus Jensen on the rocky beach, as if holding someone’s hand. We constitute a petric tandem, establishing a lapidary connection, we are entangled and intertwined like the trunks of willows growing next to the house. The root of the word stone is solid, stoi-no-, the suffix form of the root stai- or "stone," also "to thicken, stiffen" (the source also of Sanskrit styayate, "curdles, becomes hard," while the Greeks meant a "fat, tallow,", and behind stia, stion, they meant what we do when we say "pebble." A stone was a measure of weight. A petrified testicle. A source of imagination. The stone i find at the north tip of the island, covered in cotton material by Susanne Irene Fjørtoft, looks like the pillow which served Jacob in his sleep and brought him a vision. Or it is a challenge for struggling, frustrated sculptors.

When we wish to be direct and cut it short, we are lapidary like a stone, lapis in Latin, which may be connected with the Ancient Greek λέπας (lépas, “bare rock, crag”), which in turn comes from Proto-Indo-European lep- (“to peel”). Poets always believe in peeling the stones, they imagine they get to their stony souls, discover their stony universes, sneak into their rocky, hard hearts and later tell us tasty, juicy truth about stones’ cores, indifference and ignorance. While the stones, they outsmart us with their wise silence.

alicja rosé

alicja rosé is a poet and illustrator. Her books with illustrations were nominated and received major awards in Poland.

She has just published a book of poetry with illustrations "Północ. Przypowieści" (North. Parables), Znak Publishing House 2019.

Portfolio: alicjarose.com

alicja rosé

alicja rosé is a poet and illustrator. Her books with illustrations were nominated and received major awards in Poland.

She has just published a book of poetry with illustrations "Północ. Przypowieści" (North. Parables), Znak Publishing House 2019.

Portfolio: alicjarose.com